Shelter

THE AIR-RAID SHELTER ON THE CAMÍ D’ONDA

..

5 keys to understanding the bombing of Burriana and the construction of the shelter

1

Who bombed Burriana?

From the beginning of the war, the strategic importance of aviation was evident, and both sides sought to gain air superiority, which would be crucial for the outcome of the conflict; on the Republican side, they had the Spanish Republican Air Force (FARE), while the forces led by Francisco Franco had the National Air Force. However, these forces were insufficient and their aircraft obsolete.

As the war progressed, both received foreign reinforcements in the form of aircraft and pilots, such as those from Mussolini’s Italy which, a week after the war began, led part of Franco’s army to cross the Strait of Gibraltar from Tetuan along with German aircraft. In addition, in mid-August an expeditionary air force was established in Palma de Mallorca with several naval air bases from which both Franco’s Italian and German ships and aircraft operated, although incursions also came from airfields in the interior of the peninsula. Additionally, the Republican War Ministry requested aid from the USSR, which also provided a large fleet of aircraft such as Polikarpov fighters and Tupolev Katiuskas bombers.

Franco’s bombing actions over the Valencian coast would be carried out in two phases: the first would be carried out by the Italian Legionary Aviation of the Balearic Islands, with the aim of slowing down or hindering the offensive of the Popular Army of the Republic over Teruel between December 1937 and February 1938, by the 8th Squadron; for this purpose, mainly Cant Z 501 bombers and the Savoia Marchetti SM-79 or SM-81 would be used. The second phase, from March 1938 until July, would support the advance of Franco’s army in its advance towards the Mediterranean and during the Levante Offensive, with the partaking of the German Condor Legion with Heinkel He-111 or Dornier Do-17 aircraft.

We should not forget the air attacks by the Republican air force which, as it retreated and lost ground, carried out harassment actions against the towns that were in the hands of Franco’s troops; these actions were carried out in our area with Potez or Fokers aircraft.

Savoia SM-79 bombers

Heinkel He-111 of the Condor Legion. Getty

Tupolev SB-2 Katiuska

2

Why was it bombed?

In the mid-1930s, Burriana, capital of la Plana region, was a large agricultural and industrial town of some 15,000 inhabitants, with an economy based on the cultivation and exploitation of citrus fruits, and a whole series of industries developed around it for trade and export. In addition to the paper and silk stamping factories, carpentry and mechanical sawmills that made boxes for export, agricultural machinery factories, confectioners, mills… there were other complementary industries such as porcelain production, construction companies, tinsmiths, vehicle repair shops, etc.

After the outbreak of war, many of the local industries were controlled by the trade unions or by the Government, and concentrated their production on sustaining the locality itself and the war effort, thus supplying the Republican army: the manufacture of wooden containers for the Agricultural Export Committee and other types of material for the army, sanitary ceramic material for the blood hospitals and electrical conduction for the Transmissions Park, workshops to provide repair and maintenance services for army vehicles with parts made by the tinsmiths, and all the port and maritime installations that would become collective and work for the Unified Levantine Committee of Agricultural Export (CLUEA). The agricultural machinery industries changed their production to manufacture war material, with a munitions factory on the banks of the river Ana in Burriana.

Among the most important infrastructures were the national road that linked Valencia with Barcelona, a route that crossed the Main Street; the line and station of the North Railways, the Steam Tramway line from Onda to Grao de Castellón (the “Panderola”, 1907) and above all the port facilities (first dock built between 1927 and 1932), from where products were exported abroad and where the production of the fishing fleet was stored. These communications crossed the river Ana and the Mijares by means of various bridges.

Burriana’s geographical location on the plain of La Plana and the confluence of infrastructures and communications along the coast and the river Mijares made the city a military target easily exposed to air raids. Also, there was to consider the militarisation of the city with the arrival of the war front, a time when buildings such as convents, churches, schools and warehouses were used as warehouses for military material, garages, militia barracks, hospitals… In addition, in the countryside, defensive positions were established in the orchards (trenches, machine gun nests) and rural buildings.

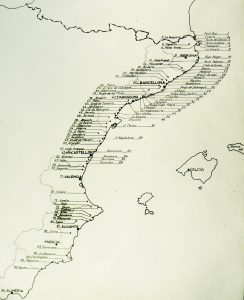

List of military targets of the Aviazione Legionaria Italiana. Municipal Archives of Valencia

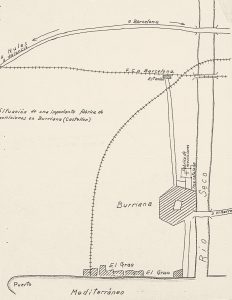

Location of an armaments factory in Burriana. AGMAV

3

When did the bombings take place?

The numerous bombings that took place over Burriana were caused by the different phases of the war.

The first bombing that Burriana suffered was carried out on March 26th 1937 by 3 Italian Cant Z-501 seaplanes, which left from bases in Mallorca to attack the port infrastructures of Castellón and Burriana, as well as the blast furnaces of Sagunto. The bombardments could also come from the sea, as there is evidence of the presence of Franco’s warships patrolling the coast of Castellón to intercept fishing or merchant ships (such as the pirate and hijacking attack on April 27th on Burriana’s fishing boats) or to fire on targets (as recorded in the Heraldo de Castellón of June 26th 1937, which reported the explosion of a shell on the road to the port).

With the preparations of the Republican army for the reconquest of Teruel, Franco’s aviation again carried out attacks on strategic targets, mainly bridges, roads, railways (such as the attacks on the station on December 22nd 1937 or April 13th 1938) or the port, with bombing raids such as that of November 29th by Savoia and Dornier seaplanes, on January 16th 1938 by Savoia 79 trimotors in which the English merchant ship Seabank Spray was affected, or that of April 1st 1938, in which Junkers JU-52 planes of the Condor Legion took part.

The next wave of attacks, until mid-June, took place in the context of the advance of Franco’s army in the so-called “Valencia Offensive” or “Battle of Levante”, and were therefore carried out by German planes of the Condor Legion with Heinkel and Dornier aircraft. These attacks were also aimed at targets located inside the city, in addition to the aforementioned infrastructures of the port and the railway station.

With the entry of the rebel troops of the 83rd Division into Burriana, the town was in Franco’s rearguard, as the front moved towards Nules. From that moment on, there were four more attacks by the Republicans, in what were known as “hot bombing raids”, carried out on recently lost ground to hinder the enemy advance and eliminate concentrations of troops or strategic objectives, such as those on the 10th, 11th, 13th and 14th of July 1938 by aircraft of the 72nd Bombardment Group.

Bombing of Burriana, November 30th 1937.

Bombardment of the Mijares bridges, December 13th 1938. Istituto Storico Parri

Bombardment of the port of Burriana, January 16th 1938. Ufficio Storico dello SME, Rome

4

The construction of shelters

The attacks on the industrial and port infrastructures during the first months of 1937 led the provincial and local authorities to take the first measures, including the first instructions to the population in cases of alarm from the Civil Government of Castellón (February 16th 1937), the proclamation of the Provincial War Board (March 24th 1937) and the instructions of the Air Defence Board.

In Burriana, the Municipal Council adopted the first measures for the protection of the population, both those of the Provincial Council and its own. On March 29th 1937, it requested the use of material from the disused La Panderola railway line for the construction of shelters, the management of which would be in the hands of the local Public Works Commission. A few weeks later, on April 16th, a request was made for the installation of a searchlight and an anti-aircraft cannon on the roof of the bell tower. Both the Railway and Tramway General Management and the Air Deputy Secretary rejected these requests.

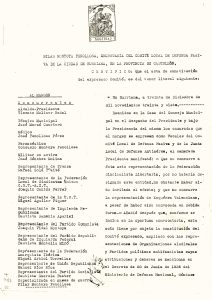

With the resumption of the attacks at the end of November 1937, the Civil Government of Castellón issued a telegram urgently ordering the constitution of local Passive Defence Committees to promote the construction of shelters. In the case of Burriana, the trade unions would be in charge of managing the building materials, the people employed (locals, refugees, young people and the elderly) and the investment of the work from the public funds, the weekly extraction of 3% of every worker’s wages and donations. On December 30th 1937, the Local Passive Defence Committee was set up in Burriana.

Faced with the danger of bombing, the Defence Councils also insisted on the creation of spaces that could offer a certain degree of security in order to accommodate as many people as possible.

The documentation issued by the Municipal Council indicates that, in May 1938, the city had at least 25 private shelters (Casa Abadía, Círculo Frutero…), with a capacity for 800 people. To these were added other public shelters such as those of the Cervantes School Group (Peñagolosa), the Municipal Market, the Pablo Iglesias School Group (shelter on the camí d’Onda) or the one at the Railway Station, bringing the total capacity to around 4000 people.

Act of constitution of the Burriana Local Passive Defence Board. CDMH

5

The population and shelters

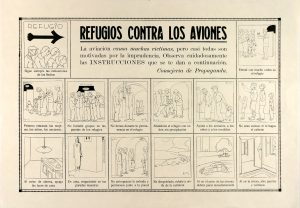

With the first attacks on the towns in the province, the Civil Government of Castellón and the Air Defence Board issued a series of instructions to warn the population. Leaflets, booklets, posters and announcements were printed and communicated.

These instructions called for the population to impose “extreme discipline and the utmost serenity” to cooperate in the general relief effort, warning any neighbours who might not have heard the alarm signal and helping children, the elderly or the sick to go to shelters marked out in the streets (with priority access for women) as well as to avoid dangerous crowds at the entrances.

At night, the street lights were turned off, as well as those in rooms or spaces facing the street or interior courtyards, using lanterns or candles inside the houses.

From the time the alarms sounded, in many cases there were only a few minutes to get to the shelters, so in practice the elderly, sick or convalescing people did not make it in time, covering them with blankets and mattresses to avoid shrapnel or crushing damage.

In the event of bombing, it was strictly forbidden to stand in the street and look out from balconies and windows. Soldiers or guards controlled the entrances to the shelters and ensured orderly entry, mitigating the effects of panic and nervousness. Inside, people remained silent, smoking and eating were forbidden, and in many cases they stood for hours in unhealthy conditions (overcrowding, poor ventilation, earth shelters, damp, cold or heat, lack of latrines, darkness), hunger and restlessness.

The bombings left an indelible mark and memory on the population, a psychological impact caused by the sound of the planes (the “turkeys”) and the explosions, the sound of the alarm itself (or of the bells ringing if the town did not have one), the accumulated stress and the emotional exhaustion of rushing quickly, suddenly and repeatedly to safety, which led some people to give up, staying at home or in bed, and also the disruption of normality and rest.

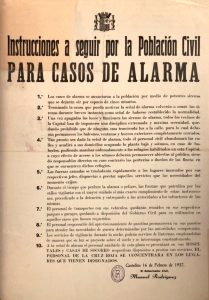

Instructions in case of alarm. Castellón, 1937

Instructions in case of alarm. Propaganda Office, 1937